Modeling the formation and distribution of trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) in the atmosphere - How a persistent chemical enters our surface waters

Dübendorf, 06.01.2026 — In collaboration with the Swiss Federal Office for the Environment (FOEN) and the University of Bern, Empa researchers have investigated how trifluoroacetic acid (TFA), the smallest of the PFAS molecules, is formed in the atmosphere and enters water bodies via precipitation. The study combined a three-year measurement period with archived water samples from recent decades and a detailed atmospheric model. The result: The release of this chemical into the environment has multiplied in recent decades – and will continue to increase in the future.

PFAS, short for per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances, are not called “forever chemicals” for nothing. These fluorine-containing organic molecules are difficult to break down and are likely to remain in the environment for decades or even centuries, where they can accumulate in humans and animals and may have harmful effects on health. This is a compelling reason to take precautionary measures.

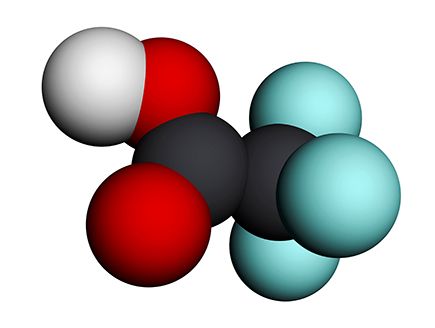

The PFAS class of substances comprises thousands of chemical compounds. Not all of them have been thoroughly studied. The release, spread, accumulation, and effects of numerous PFAS are the subject of ongoing research. Among other things, researchers are focusing on TFA, short for trifluoroacetic acid. The smallest molecule in the PFAS family is formed as a degradation product of various other substances, such as many fluorinated refrigerants and propellants. Once formed, TFA is hardly degraded in the environment. “TFA formed in the atmosphere quickly enters precipitation, and from there it travels into surface waters and then into groundwater,” says Empa researcher Stefan Reimann from the Air Pollutants / Environmental Technology laboratory.

How and where exactly TFA forms in the atmosphere and in what quantities the substance enters water bodies has remained largely unexplored to date. In a joint new study published in the journal Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics, Empa researchers, in collaboration with the Swiss Federal Office for the Environment (FOEN) and the University of Bern, investigated this question in more detail. They modeled the formation and transport pathways of TFA in the atmosphere and compared them with TFA measurements from environmental samples.

Over a period of three years, the FOEN analyzed samples of precipitation and surface water for TFA and consulted archived water samples dating back to 1984. At the same time, Empa researchers created a detailed model of the atmospheric input of TFA. “We model the known precursors of TFA, their degradation pathways and intermediate products, as well as the deposition of the TFA formed in this way, both via precipitation and directly on surfaces,” explains Empa researcher Stephan Henne, lead author of the study. The complex model allows predictions to be made over long periods of time with high spatial and temporal resolution. “For every location in Europe, we can now calculate how much TFA is released into the environment in a given month,” says Henne.

Further increase expected

The results of the study show that concentrations of TFA in precipitation and surface waters have multiplied in recent decades. According to the researchers, this is primarily due to the increased use of hydrofluoroolefins (HFOs). These fluorinated gases serve as refrigerants and propellants, replacing climate-warming hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs) in this role. Unlike long-lived HFCs, HFOs decompose quickly in the atmosphere – among other things, into TFA. “As the use of HFOs in refrigeration and air conditioning systems continues to increase, we assume that TFA deposition will also rise in the future,” says Reimann.

Another significant source of TFA is the degradation of pesticides – in this case, however, the substance does not take a detour via the atmosphere but enters the water more or less directly via the soil. “Once TFA is in the water, it remains there almost without exception,” adds Stephan Henne. The final accumulation site for the persistent fluorinated acid is therefore the ocean.

In addition to providing answers, the study also raises new questions. “Our model explains around two-thirds of the total measured atmospheric input of TFA,” says Stephan Henne. “This means that there are probably other precursor substances and formation pathways that we are not yet aware of.” This is also supported by the fact that TFA is present even in historic precipitation samples, albeit in much lower concentrations than today. However, the known precursors have only been in use since the 1990s. In the future, the researchers want to take a closer look at these as yet unknown precursors and incorporate them into their atmospheric model.The extent to which TFA is harmful to living organisms, including humans, has not yet been conclusively researched. Some recent studies provide evidence of possible long-term toxicity. “TFA is very persistent, accumulates more and more in our water, and is almost impossible to remove,” warns Reimann. “We should therefore act in accordance with the precautionary principle and restrict the use of precursor substances as much as possible.”

PFAS, the forever chemicals

The PFAS class of substances comprises thousands of chemical compounds. They contain fluorocarbon bonds, and many of them are known to be extremely stable, meaning that they hardly decompose in the environment. The health effects of PFAS are not yet fully understood, but they are associated with a variety of diseases, from organ damage to cancer. In the new Pocket Facts, Empa, Eawag, and the Ecotox Center provide information about these forever chemicals and how they can be avoided.

https://www.empa.ch/web/pfas/overview

Further information

Dr. Stephan Henne

Empa, Air Pollution / Environmental Technology

Phone +41 58 765 46 28

stephan.henne@empa.ch

Dr. Stefan Reimann

Empa, Air Pollution / Environmental Technology

Phone +41 58 765 46 38

stefan.reimann@empa.ch

Prof. em. Dr. Markus Leuenberger

Universität Bern

markus.leuenberger@unibe.ch

Literature

S Henne, FR Storck, H Wöhrnschimmel, M Leuenberger, MK Vollmer, S Reimann: Trifluoroacetate (TFA) in Precipitation and Surface Waters in Switzerland: Trends, Source Attribution, and Budget; Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics (2025); doi: 10.5194/acp-25-18157-2025